If you are saving up for retirement, you are probably planning on a Safe Withdrawal Rate between 3 and 4%. Where does this come from?

As physicians, we love to see the evidence behind recommendations. Here’s a little bit about the Safe Withdrawal Rate.

The origin of the Safe Withdrawal Rate comes from a study by William P. Bengen, titled Determining Withdrawal Rates Using Historical Data, published in the Journal of Financial Planning in October 1994.

Bengen: The Man

Bengen’s story itself is quite amazing. He studied to be an aeronautical engineer at MIT but joined his family’s soda-bottling business in New York. He stayed for 17 years, presiding over the business in the later years, until it was sold. He then moved his family all the way to California and started an encore career as a financial planner in 1987. Many of his clients were baby boomers, close to retirement. And they wanted to know how to spend in their retirement years in order to avoid running out of money.

Setting The Scene

In the early 90’s, it was common to think that one could spend the average returns of the market in a year. That way, one would be spending the earnings or growth and not the principal.

The average stock return was 10.3%, bond returns was 5.1%. So a 60:40 stock:bond portfolio returned 8.2% compounded per year. And inflation was 3%. Retirees were therefore advised to withdraw 5% a year.

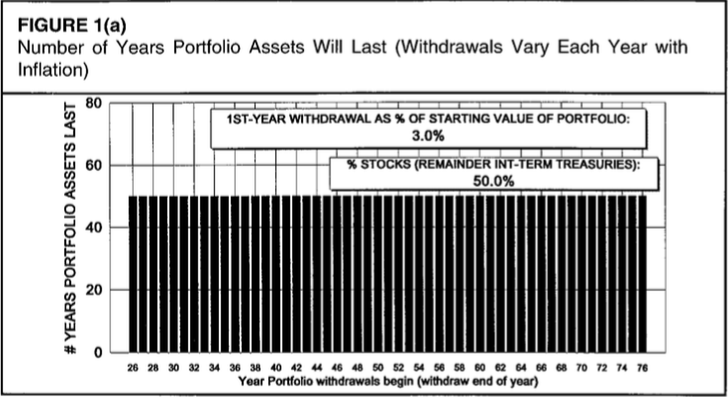

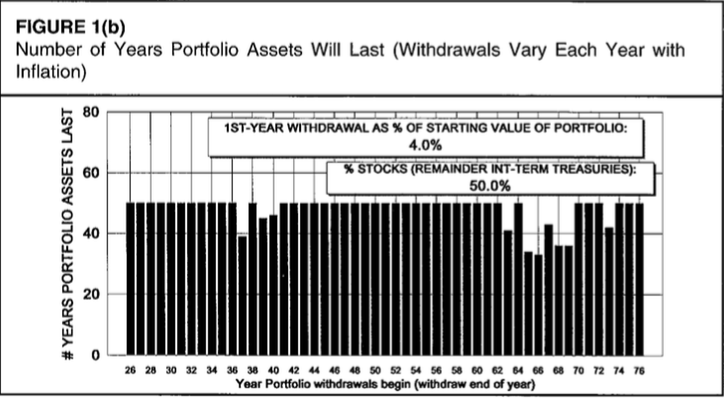

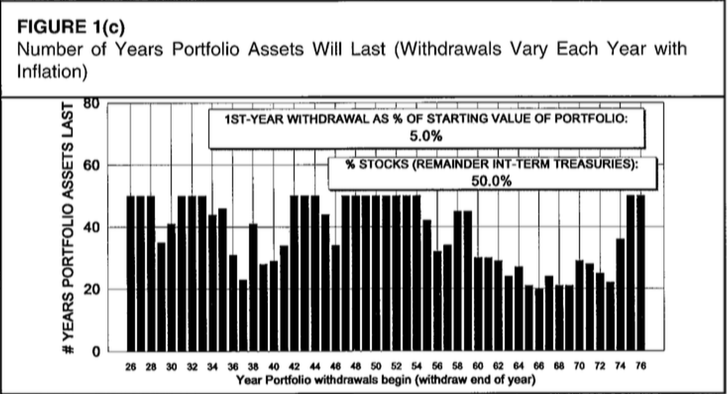

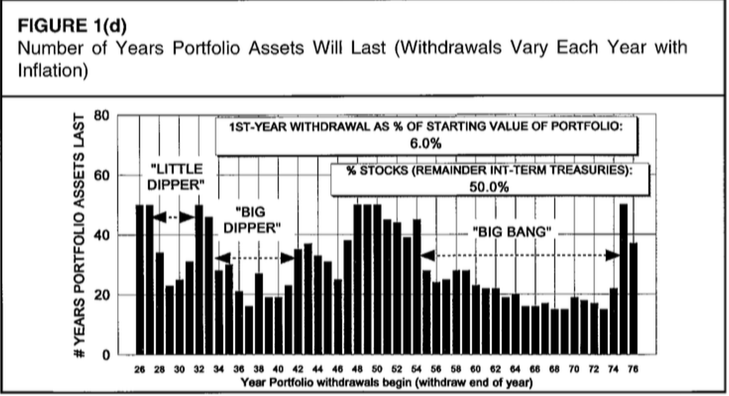

Bengen wanted to find out how these portfolios behaved. He pulled together data from 1926 to 1992. And this is what he found:

Withdrawal Rate and Portfolio Longevity

The recommended high withdrawal rates worked just fine as long as the markets behaved close to average. But when a market catastrophe hit, the average got overwhelmed. The three biggest events within the time frame studied were the Great Depression, World War 2 and the stagflation of the 1970’s. Interestingly, it was the last event that wrecked the greatest havoc on portfolios because of the combination of poor market returns and inflation.

Bengen considered a 50:50 stock:bond portfolio. The stock portion was composed of large company stocks. The bond portion was composed of Intermediate term Treasuries.

He found that with a 3% withdrawal rate, adjusted for inflation, the portfolio lasted for 50 years or longer.

With 4% withdrawal rate, during the big market downturns mentioned above, portfolio longevity decreased. Even then, the shortest portfolio duration was 33 years.

Withdrawal rates of 5% and 6% were not sustainable, in his findings.

Some portfolios got exhausted within 20 years- if they happened to fall within the time frame of the big three.

From the above, Bengen concluded that for a 50:50 stock:bond portfolio, an annual withdrawal of 4% of the initial portfolio value, and adjusted for inflation in subsequent years, was safe since it was most likely to last throughout a retiree’s life.

And that was the birth of the 4% Rule.

Portfolio Longevity and Asset Allocation

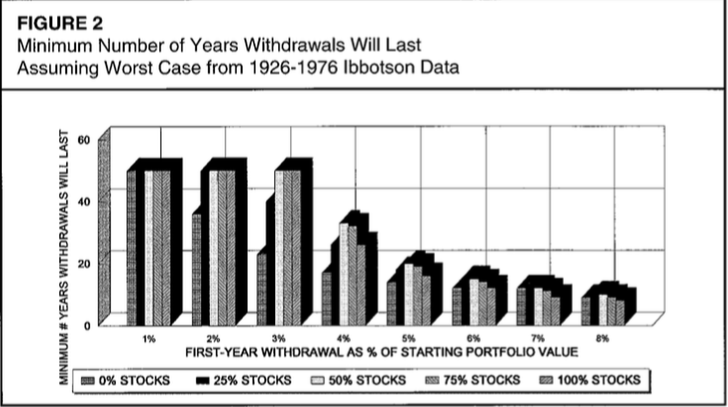

The above conclusions came from assuming a 50:50 stock:bond portfolio. How about other asset allocations? Surprisingly, higher stock portfolios seemed to do better than lower stock ones.

And the 50:50 allocation appears to do best, especially in the more relevant 4-5% withdrawal rates.

But from this graph, the 75% stock portfolio performance is right on the heels of the 50% stock portfolio. But is there anything to gain from going up on stocks in the portfolio beyond 50%?

Yes. 75% stock portfolios had even higher longevities than 50% stock portfolios for 4 and 5% withdrawal rates. The trade-off is that they declined more sharply during big bear markets, as expected. But even under these circumstances, all portfolios lasted longer than 30 years.

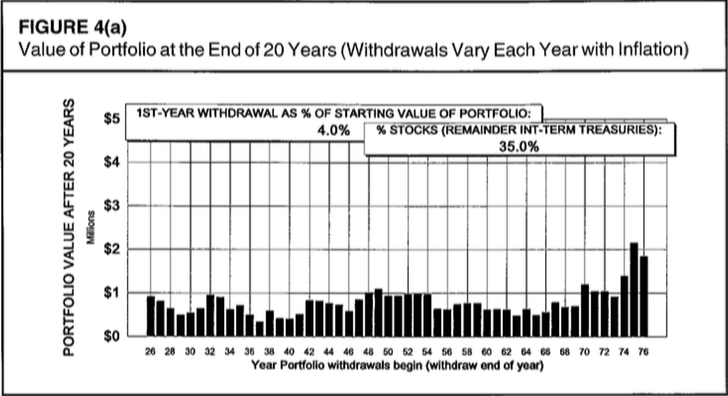

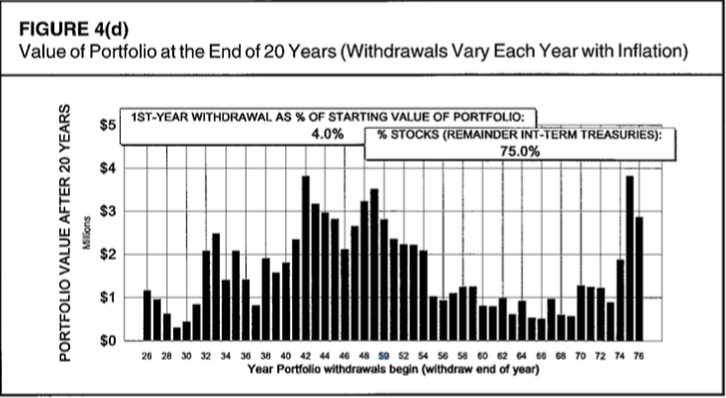

Another consideration: wealth accumulation. The difference between portfolio values with 35% stocks versus 75% stocks was stark, as the figures below show.

Based on all of this, Bengen recommended a stock allocation between 50 and 75%, based on one’s risk tolerance.

Even In Retirement, Stay The Course

As throughout the accumulation period, it is important to stay on track during retirement years. Most of the time, there is no reason to change the asset allocation. It is especially important not to back out of stocks at the bottom of the market. That behavior may cause you to run out of money before you run out of breath.

Those who have a stellar few years at the beginning of retirement are advised not to increase withdrawal rates recklessly. Those increased returns will be needed to offset the decline in down years.

And those who are unlucky in their returns in early retirement will only lock in their losses if they bail out of the market when it is low (sounds familiar). In fact, if a retiree has the fortitude to increase stock allocation at such times, they amass a great deal of wealth at the end of retirement.

This is, in a nutshell, Bengen’s fascinating study- which brought the famous 4% Rule into existence.

In the next post, we will delve into another seminal study in this field: the Trinity Study.

Thanks for reading!